How to apply VBHC with Healthcare workers in EU?

By Dr. Rostand Idriss Tchana

As we’re living in a world where the connection between patients and their caregivers is really the main point of the healthcare system as creating a meaningful understanding of the pathology from the patient and building the trust with the caregiver. It’s definitely interesting to highlight the positive outcomes and the values that we can have in clinical practice.

First thing first, regarding the healthcare system having more inclusiveness and use of cultural background and patient’s intellectual asset is a helpful tool to optimize the therapeutic journey. This process is in both ways first the caregiver knowing the patient background and using meaningful words to make him understand the medical procedure or his pathology; Then patient understanding and trusting his caregiver.

A major challenge in value-based health care is the lack of standardized health outcomes and relatedness with health settings globally.1 Somehow, there is then a priority to add integrative tools to develop a standard set of value-based patient-centered outcomes in the healthcare system.

Elements such as social, economic, and environmental disadvantages, cultural beliefs and religion lead to health disparities and impact patient’s health literacy levels.13 Therefore, several tools are implemented on the system to make sure this part is not avoided in the caring process :

`

i. Patient inclusive practice and SDM:

Inclusion of the patient in the process of decision making of the primary care physicians and specialists and the use of several methods as the “teach back”2,”Colleague assessment reformulation”2 “illustrations”3. The caregivers community recognized the pervasiveness of this issue and developed solutions to improve patient-clinician communication, increase cultural competencies of providers, and ensure comprehension of material across different population demographics. Meanwhile, providers could develop and implement processes to survey the literacy levels of their patient population and the reading level of their materials, and ensure alignment.3

SDM can also be applied to patient–clinician discussions about guidelines for effective care in which the evidence on a population level strongly favors a health behavior. There are many sources of uncertainty that can arise when translating evidence-based population-based risk/benefit estimates to individual patients in real-world practice.7-8 Recommendations based on tightly controlled randomized trials in highly selected patient populations might not all apply at the individual patient level. For example, although guidelines for colorectal cancer screening suggest that individuals receive either colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or fecal occult blood test (FOBT) beginning at the age of 50,5 for some individual patients, one test could be superior to another. Some patients might not feel able to go through some medical procedures or not have access to a trained clinician and others might have a history of bleeding and can even refuse FOBT as they can risk multiple false positive results, requiring additional follow-up procedures. Although it is really obvious that communicating and explaining the difference between population and individual estimated risk or benefit might discourage patients from engaging in recommended practices, communicating this information through SDM can actually benefit clinicians and patients when discussing guidelines. Providing patients with information about risks and their associated uncertainty, and acknowledging the limitations of epidemiologic data as applied to individuals, clinicians can help patients make sense of the wealth of prevention data available as they work together to make individual decisions about their health.8-9 There is also proof a more satisfaction from patients using the SDM, improving the patient–clinician relationship if data and its uncertainty are expressed and managed with transparency.10-11 Patients might be more willing to adhere to the mutually agreed-upon plan if they have a better understanding of their options.7 SDM supports a tailored clinician–patient discussion about evidence, rather than placing the burden on patients to resolve uncertainty on their own.12

ii. Online literacy and digitalization:

With the development of digitalization and access to a lot of online information for educational purpose, is the goal of a lot of EU initiatives patient oriented to improve the Healthcare system by providing more information to the patient raising and awareness on online materials and the raise of fake news.3 As we have a lot of fake news platforms and websites developing misinformation of populations, selected databank of right websites with interesting content and accessible elements are produced sometimes are sometimes patients initiatives. Social networks have also been lately a place where patients can inform themselves on different pathologies, treatments and risks. In LMICs for example the use of the social network has proved efficient in the prevention of several pathologies.4

eHealth is a reality and is taking part in most of the daily activities in the healthcare system in Europe and brought a lot of efficiency and rapidity in the caregiving process. Meanwhile some elements need to be implemented to have better results. A study from Marianne P. VOOGT and al. in the Dutch healthcare system raised different points that needed to be implemented to have better results or the total trust of users both sides, caregivers or patient: reimbursement fees, high fees to online materials, limited application of the intervention during time, insufficient resources for end-user involvement, lack of autonomy and Mismatch.5

iii. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA)

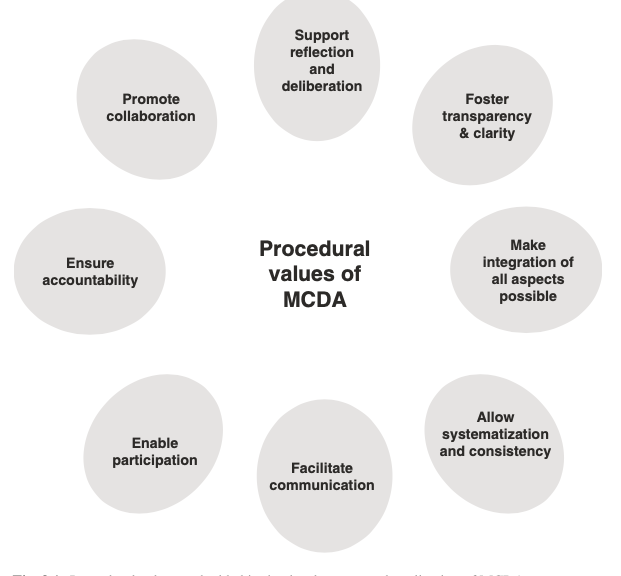

Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) is a process that can definitely to support better healthcare decision making. This process needs to overcome several challenges before revealing its huge potential. The process of multidisciplinary therapies strategies in health process is definitely something that helps shaping this at his best.14 The different challenge expressed are both technical – which weighting methods are most appropriate and how should uncertainty be dealt with – and political, the need to work with decision makers to get their support for such approaches. When comparing healthcare technologies, decision-makers often need to make trade-offs between these criteria. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) is a tool that helps decision-makers summarize complex value trade-offs in a way that is consistent and transparent. It consists of a set of techniques that bring about an ordering of alternative decisions from most to least preferred, where each technology is ranked based on the extent to which it creates value through achieving a set of policy objectives.14 We can have a view on the procedural values of MCDA as illustrated in Fig.1. MCDA allows capturing the perspectives of all participants in a structured manner, thus clarifying the individual and group reasoning and supporting deliberation among all committee members, which is hard to achieve without an appropriate method. By the same token, MCDA can be used to consult large groups of individuals.4-14

MCDA has the potential to address a number of limitations of current HTA systems, most importantly, being more explicit in the way multiple attributes of value beyond improvements in health are taken into account; reflecting social values; providing more systematic and robust ways of considering evidence from stakeholders; and supporting the way HTA decision makers exercise judgement when making trade-offs between multiple criteria.14 HTA processes typically seek to maximise ‘value’ given limited health-care resources. However, what is considered to constitute ‘value’ can vary among jurisdictions and from a country to another. There is general consensus that improvements in health as a result of treatment is the most important benefit: many HTA systems have introduced highly formalised approaches to measure changes in patient health and for choosing interventions that are effective and provide value for money. Those systems, set up in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, European Nordic countries such as Sweden and some Canadian provinces, have primarily relied on the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) for measuring changes in both length and quality of life and focused on its maximisation in their decision making processes.

i. Value based in Healthcare

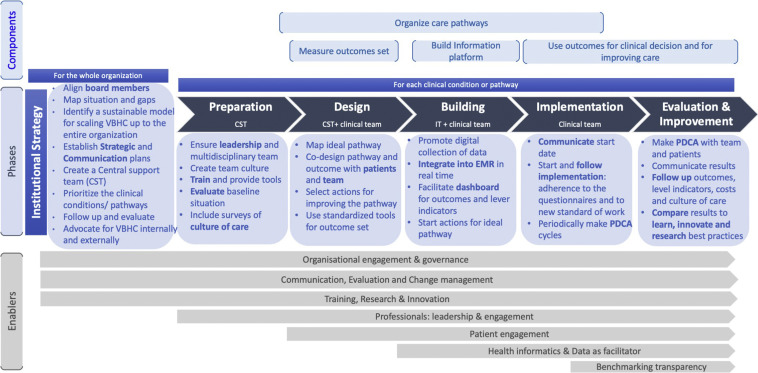

value-based healthcare (VBHC) aims at improving patient outcomes while optimizing the use of hospitals’ resources among medical personnel, administrations, and support services through an evidence-based, collaborative approach. Thus this process is facing some difficulties to give best results and being implemented sometimes and needs the caregivers, the administrative pool and all the workers board of the system to get together for having great results.15-16

This process in medical hospital can be implemented through six phases as presented on the blueprint of Yolima Cossio and al (Fig).2.16

– Phase 1: Preparation of the Whole Organization for VBHC: Institutional Strategy (CFIR Domain: Inner Setting)

– Phase 2: Preparation of Each Clinical Pathway (CFIR Domain: Process)

– Phase 3: Design (by the CST and the Clinical Team; CFIR Domains: Process and Individuals Involved)

– Phase 4: Building (by the IT and the Clinical Team; CFIR Domains: Settings [Inner and Outer] and Individuals Involved)

– Phase 5: Implementing (by the Clinical Teams; CFIR Domains: Process and Individuals Involved)

– Phase 6: Evaluation and Improvement (CFIR Domains: Settings [Inner and Outer] and Process)

Observations on the cost-effectiveness for decision making, the lack of clarity on strategic priorities And several observations were made regarding the VBHC and its implementation as lack of management skills, misunderstanding of the progressing as expected and if generating “value” and engagement on the VBHC were different points referred as barriers of the VBHC implementation regarding the organizational engagement and governance, communication and management. Some other points were also highlighted regarding the patient and the tool used. This mean a better training session should be done and transparency should definitely be implemented in the process to have better outcomes for the patient and the system itself. It’s definitely important to have then in the healthcare system decision makers that can welcome at best change and VBHC. We can then ask ourselves if hospital managers are ready for value-based healthcare?

References :

1. Ong WL, Schouwenburg MG, van Bommel AC, et al. A Standard Set of Value-Based Patient-Centered Outcomes for Breast Cancer: The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) Initiative. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(5):677–685. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4851

2. Furlough, Kenneth A et al. “Value-based Healthcare: Health Literacy’s Impact on Orthopaedic Care Delivery and Community Viability.” Clinical orthopaedics and related research vol. 478,9 (2020): 1984-1986. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000001397

3. John J., (1996), “A dramaturgical view of the health care service encounter: Cultural value‐based impression management guidelines for medical professional behaviour”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 30 No. 9, pp. 60-74. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569610130043

4. Perkins JM, Subramanian SV, Christakis NA. Social networks and health: a systematic review of sociocentric network studies in low- and middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015 Jan;125:60-78. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.019. Epub 2014 Aug 19. PMID: 25442969; PMCID:

5. Marianne P. VOOGTa,1, Brent C. OPMEERb , Arnoud W. KASTELEINc , Monique W.M. JASPERSa,d and Linda W. PEUTE. Obstacles to Successful Implementation of eHealth Applications into Clinical Practice. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-852-5-521

6. Politi MC, Han PKJ, Col NF. Communicating the uncertainty of harms and benefits of medical interventions. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:681–95.

7. Djulbegovic B, Paul A. From efficacy to effectiveness in the face of uncertainty. JAMA. 2011;305:2005–6.

8. Coylewright M, Montori V, Ting HH. Patient-centered shared decision making: a public imperative. Am J Med. 2012;125:545–7.

9. Boivin A, Legare F, Gagnon MP. Competing norms: Canadian rural family physicians’ perceptions of clinical practice guidelines and shared decision-making. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13:79–84.

10. Johnson CG, Levenkron JC, Suchman AL, et al. Does physician uncertainty affect patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:144–9.

11. Parascandola M, Hawkins J, Danis M. Patient autonomy and the challenge of clinical uncertainty. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2002;12:245–64.

12. Politi, M.C., Wolin, K.Y. & Légaré, F. Implementing Clinical Practice Guidelines About Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Through Shared Decision Making. J GEN INTERN MED 28, 838–844 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2321-0

13. Shafranske, E. P ., & Malony, H . N. (1996). Religion and the clinical practice of psychology: A case for inclusion. In E. P. Shafranske (Ed.), Religion and the clinical practice of psychology (pp. 561–586). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10199-041

14. Kevin Marsh, Mireille Goetghebeur, Praveen Thokala, Rob Baltussen, Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis to Support Healthcare Decisions

15. Walsh, A.P., Harrington, D. and Hines, P. (2020), “Are hospital managers ready for value-based healthcare? A review of the management competence literature”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 49-65. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-01-2019-1639

16. Yolima Cossio-Gil, Maisa Omara, Carolina Watson, Joseph Casey, Alexandre Chakhunashvili, María Gutiérrez-San Miguel, Pascal Kahlem, Samuel Keuchkerian, Valerie Kirchberger, Virginie Luce-Garnier, Dominik Michiels, Matteo Moro, Barbara Philipp-Jaschek, Simona Sancini, Jan Hazelzet, Tanja Stamm, The Roadmap for Implementing Value-Based Healthcare in European University Hospitals—Consensus Report and Recommendations,Value in Health, 2021,